Rayon: The Fiber That Just Won’t Go Away

By Aaron Groseclose

Cleaners have encountered rayon in upholstery fabric for years. But designers also, unfortunately, increasingly embrace the silk-like look of rayon for rugs.

Rayon rugs present many cleaning challenges. This fiber does not hold up to foot traffic or consumer, do-it-yourself spotting/cleaning. Professional cleaning may exacerbate pre-existing texture distortion and sprouting.

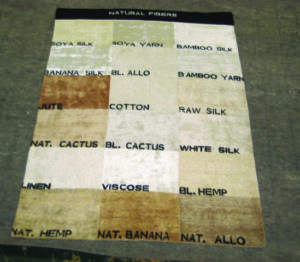

Technicians can attend advanced rug cleaning courses that demonstrate methods to clean rayon and silk rugs and correct texture distortion. (See Image 1.)

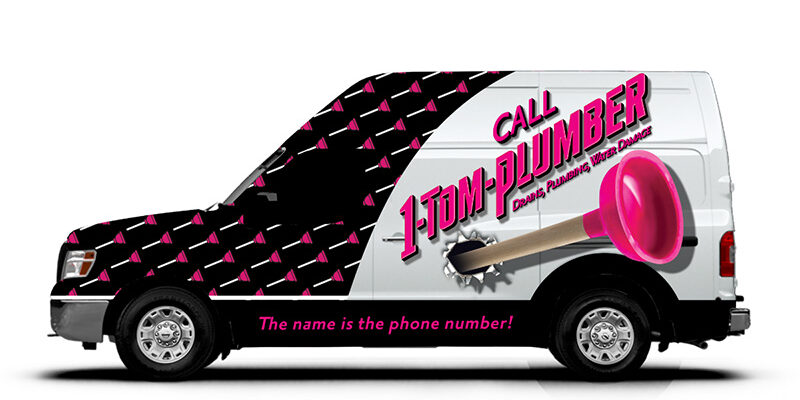

Another problem associated with rayon rugs is that the dyes are not always colorfast. There have also been instances of pattern stencil bleeding/wicking to the face and back from the foundation yarns. (See Image 2.) This stencil bleeding cannot be predicted or tested for prior to cleaning.

It is important to be clear with customers to avoid misunderstandings, communicating that these issues are pre-existing conditions. You should obtain a written release before cleaning these rugs.

Rayon is known by several names: Artificial silk, art silk, banana silk, viscose, bamboo silk, allo silk, cactus silk, soya silk, modal, cuprammonium, lyocell, and Tencel.™ All are a type of rayon manufactured from regenerated (or reformed) cellulose. (See image 3.)

There are four main processes to produce rayon.

1 | Regular rayon or viscose

Searching for a product that could match the look of silk, a Frenchman by the name of Count Hilaire de Chardonnet produced the first manufactured fiber. In 1891, he dissolved the pulp of mulberry trees (since silk worms feed on the leaves) in chemicals and forced the solution through a metal plate with tiny holes. It was then exposed to heated air and chemicals to harden the material into a filament fiber. He patented the process of making “artificial silk,” which was a shiny fiber. However, it was removed from the market due to flammability issues.

Large-scale commercial production of “artificial silk” began around 1900 based on a process developed by British inventors, Charles Cross, Edward Bevan, and Clayton Beadle. Cellulose from wood pulp, or short cotton fibers called “linters,” are immersed in a solution of sodium hydroxide (caustic soda) and aged for a time. This results in a solution that is thick and viscose, which gives us the term viscose rayon. Then the fibers are forced through a spinneret into a bath of sulfuric acid to harden the material.

The confusion between real silk and artificial silk led the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, or FTC, (more on this later) in 1924 to establish the term “rayon” for regenerated cellulosic fibers. The term rayon means “ray of light” in French. This term is mostly used in the U.S., and “viscose” is the common term in Europe. For our purposes, we will use the term “viscose rayon.”

Because of environmental problems associated with the process, viscose rayon is no longer manufactured in the USA. The viscose process is still the most common method of worldwide production, which is now mostly performed in Asia. India is the largest manufacturer of the fiber for use in garments, rugs, etc.

2 | High Wet Modulus (HWM), Modal

A Japanese researcher modified the viscose process to develop a fiber with a physical structure more like that of cotton — a greater resistance to deformation when wet. Modal is used for activewear garments and a high-tenacity (high-strength) version of tire cords.

3 | Lyocell

The raw material for lyocell, like that of viscose rayon, is cellulosic pulp. The chemicals used are not as toxic as viscose rayon, and the process is self-contained.

Lyocell fiber is stronger than viscose rayon and is mostly used in garments. It can be sold under the brand name Tencel and is manufactured mostly in Europe. Recently, Tencel came to market for carpet and rugs since it feels “silky and soft.” Tencel, when used for garments, will shrink 3 percent after the first washing. This is not a problem for rug cleaners unless it is used in the backing or foundation yarns.

Some sales people tell their customers Tencel is not rayon, but at the end of the day, it is a type of regenerated fiber with cleaning issues similar to viscose rayon.

4 | Cuprammonium rayon

The process for developing cuprammonium rayon is different from the viscose rayon process. In the cuprammonium process, cellulose is dissolved in a copper ammonium solution, and the fiber is extruded into a water bath. It is somewhat more silk-like in appearance than viscose rayon and a bit stronger. The fiber is made mostly into lightweight fabrics. Due to clean-water regulations, it is no longer produced in the USA.

Rayon in rugs

What we commonly encounter as rug cleaners is either viscose rayon used as a design highlight, woven carpet fabricated into an area rug, or rugs made from 100 percent viscose rayon. The label could read “artificial silk” or be abbreviated as “art silk.” Unfortunately, many consumers overlook the “art” part of the label and are convinced they have a true, silk rug. They might have paid a considerable amount of money for the rug (particularly if the rug dealer was not forthcoming).

A viscose rayon rug may have pre-existing pile distortion and sprouts, so be sure to document that on your inspection form. Discuss this issue with your customer. Cleaning may not improve the look and may create additional distortion and sprouts. During the cleaning process, viscose rayon, when wet, loses 30 to 50 percent of its strength, according to the apparel/ textile industry’s Fabric University.

The back-and-forth movement of a carpet cleaning wand or rotary brush can cause pile distortion, and high-water pressure makes the damage worse. Hot water can cause the viscose rayon to bleed, particularly if it contains bold colors. Turning down the pressure and heat and avoiding the typical back-and-forth wand movement used in wall-to-wall carpet cleaning is recommended. The Achilles heel of viscose rayon is the low, wet strength. Other natural fibers such as cotton and wool have a higher tenacity.

After cleaning viscose rayon rugs, set the pile towards the bottom of the rug (that is, pile down) with a good carting brush. (See image 4.) Vacuum the rug the next day when the rug is dry (See image 5.) to lift and soften the pile. Be aware that UV light can weaken the fiber over time.

Stain removal on viscose rayon rugs can be tricky. The safest product to use is 3 percent hydrogen peroxide. (See image 6.) The rug can be placed in direct sunlight to accelerate the material, but that can lighten the fiber, so proceed with caution.

Other rayons

What about banana silk, bamboo silk, and soya silk? Trust me, bananas do not have silk. These are marketing terms used to disguise the fact that the rug is made from regenerated cellulose, i.e. viscose rayon.

Our friends at the FTC have taken several large retailers and manufacturers to court over false labeling. They have called it bamboo-zling. Maybe they do have a sense of humor after all. The FTC has been paid million-dollar fines for advertising of items “made from 100 percent bamboo fiber,” “antimicrobial fiber,” “biodegradable fiber,” and “eco-friendly fiber.” This includes such companies as Amazon, Leon Max, Macy’s, Sears, and Kmart, who continued to make those advertising claims after the FTC sent them a warning letter. The proper label for these items is “rayon made from bamboo” — it is not a “green” fiber.

As you can see, viscose rayon is a problematic fiber. Read the label if it is still on the rug. Doing a simple burn test will tell you if it is real silk (burning hair odor) or rayon (burning paper odor). Silk has problems, too, which we will cover in a future article.

Aaron Groseclose is the former president of MasterBlend, a manufacturer of rug and carpet cleaning chemicals and equipment. He instructs carpet, upholstery, and oriental rug cleaning seminars. He is the co-developer of the Master Rug Cleaner Program and co-author of A Comprehensive Guide to Oriental and Specialty Rug Cleaning.